The second post in my Dracula Series.

Existential. Pretentious. Sexy. When I see these three words in a blurb I assume I’ll love the film. And that was certainly the case with Michael Almereyda’s Nadja. “Hal Hartley meets David Lynch” says the Chicago Review. Shot in black and white, almost like a film noir, philosophical riffs are delivered with deadpan irony. Lonely, isolated characters touch each other briefly, and for a moment they seem to really communicate, but then their own alienating drama pulls them back into themselves. Everyone exudes empathy but disregards sympathy. Everyone’s a protagonist. Everyone’s heart is bleeding. Everyone’s consumed.

Existential. Pretentious. Sexy. When I see these three words in a blurb I assume I’ll love the film. And that was certainly the case with Michael Almereyda’s Nadja. “Hal Hartley meets David Lynch” says the Chicago Review. Shot in black and white, almost like a film noir, philosophical riffs are delivered with deadpan irony. Lonely, isolated characters touch each other briefly, and for a moment they seem to really communicate, but then their own alienating drama pulls them back into themselves. Everyone exudes empathy but disregards sympathy. Everyone’s a protagonist. Everyone’s heart is bleeding. Everyone’s consumed.

But for a vampire movie, there is very little blood or human consumption.

The film opens with Nadja, Count Dracula’s daughter, picking up a man at a bar. She’s discussing the difference between European cities and New York, the city she inhabits, the city she embodies. She gets him alone and the camera pixilates as she feeds, as the man dies, Nadja receives a “psychic fax” from her father, who is dying. Still pixilated, we see him stumble down a street, wooden stake sticking out of his chest. “My father is dead.”

Killed by none other than Van Helsing, but a parody of Van Helsing. In the Annotated Dracula, I read many a footnote questioning Dr. Van Helsing’s version of medical knowledge. Apparently, a great deal of Van Helsing’s medical practices, for instance, pumping Lucy full of four different men’s blood without being at all concerned whether or not any would poison her, were outdated for modern Victorian standards. Van Helsing cared more about philosophy, more about chasing vampires, than medical science. He was blunt and matter-of-fact but this came across more humorous and cold as opposed to serious and thoughtful. Many papers have been written on him as a fraud, or even an unprofessional boob, and Almereyda chose to represent him in the latter’s clothes, as the bicycle-loving, long haired eccentric, whose special vampire detecting gear boils down to a pair of John Lennon sunglasses.

Though Dracula is depicted as hundreds of years old, Van Helsing is not, and while tinkering with Bram Stoker’s narrative is not uncommon, exhibiting Dracula, as both a character imprisoned inside a text and as an ubiquitous culture icon reaching outside of the text, is a postmodern phenomenon.

Nadja is an early nineties stylized indie film. And just as Nadja is Dracula’s daughter, Nadja is Dracula’s daughter. As Van Helsing tells us, Nadja is one of many children. Just as Nadja is one of many texts carrying on the count’s legacy.

Van Helsing’s nephew, Jim, is married to Lucy. Lucy doesn’t like Van Helsing, so Jim tells her to stay home while he goes and bails his uncle out of jail for driving a stake through Dracula’s heart. Van Helsing relays the tale, as if he were simply regurgitating a myth, and Jim tells him that it seems as though he’s gone through something but hasn’t come out the other side. Van Helsing’s story is a burden to Jim, it’s what keeps him away from Lucy, but it seems to essentially bore him. All Jim’s concerned with is how unmoved his “demented,” as Lucy put it, uncle is. And though Van Helsing’s supernatural tale is exciting and interesting, especially since we know he isn’t spinning any yarn, we end up siding with Jim, possibly because the story of Dracula is exhausted. It’s old and stale, like Van Helsing and Dracula, its time is over. They are mere figureheads, settings, moods for new texts to stand in their place. As Van Helsing says about Dracula, “like Elvis at the end. Drugged, confused, surrounded by zombies. He was just going through the motions. The magic was gone. And he knew it.”

Van Helsing’s nephew, Jim, is married to Lucy. Lucy doesn’t like Van Helsing, so Jim tells her to stay home while he goes and bails his uncle out of jail for driving a stake through Dracula’s heart. Van Helsing relays the tale, as if he were simply regurgitating a myth, and Jim tells him that it seems as though he’s gone through something but hasn’t come out the other side. Van Helsing’s story is a burden to Jim, it’s what keeps him away from Lucy, but it seems to essentially bore him. All Jim’s concerned with is how unmoved his “demented,” as Lucy put it, uncle is. And though Van Helsing’s supernatural tale is exciting and interesting, especially since we know he isn’t spinning any yarn, we end up siding with Jim, possibly because the story of Dracula is exhausted. It’s old and stale, like Van Helsing and Dracula, its time is over. They are mere figureheads, settings, moods for new texts to stand in their place. As Van Helsing says about Dracula, “like Elvis at the end. Drugged, confused, surrounded by zombies. He was just going through the motions. The magic was gone. And he knew it.”

Nadja is about the children. It’s about Jim and Lucy, Nadja, Renfield, Edgar, and Cassandra. Lucy and Renfield both echo the original Lucy and Renfield, just as Van Helsing echoes Van Helsing. This is to keep us grounded in the Dracula metaphor, to remind us that the past is prologue, that the present is doomed to repeat the past’s mistakes, especially if they were never understood.

Nadja wants to change her life. She’s sick of killing for the sake of killing, of living her father’s life. She walks down the street, Portishead plays in the background. I’ve got nobody on my side and surely that ain’t right.

Lucy, as the perpetual victim, as the blonde innocent, is seduced by the vampire, by the femme fatale, Nadja. They meet at a bar, exchange family traumas. Lucy’s brother is dead. Her mother is dead. Her father is born again, he doesn’t talk to Lucy. She’s familyless, rootless, she belongs with Jim.

Nadja’s mother is dead. She was a mortal who died during childbirth. Nadja’s father is dead. Nadja’s brother is gravely ill, refuses to feed, hates vampirism, hates Nadja.

Both women are anxious. They are honest and sad. Both are fascinated with the other, but their fascination is subdued. Nadja gets up, goes to the jukebox.

“Life is full of pain. But the pain I feel is the pain of fleeting joy… I’m with someone I love I feel so much joy then I have to go away, even if it’s only for a day I’m sure I’ll never see them again I feel so alone. I don’t know what’s in front of me. I can’t breathe. The pain of fleeting joy.” Nadja.

Lucy understands. She takes Nadja home. Jim isn’t there. She shows Nadja her tarantella. She shows her an ornament on her Christmas tree, an ornament of Dad, of Dracula. Lucy presses the button and scary music shakes the kitschy doll, Nadja becomes frightened. “Why do you show me that!” Lucy becomes maternal, she takes her tarantella back. Nadja apologizes. “I’m anxious,” she repeats. They take photographs and play with sparklers. Fleeting joy. They turn on the stereo, My Bloody Valentine.

Lucy understands. She takes Nadja home. Jim isn’t there. She shows Nadja her tarantella. She shows her an ornament on her Christmas tree, an ornament of Dad, of Dracula. Lucy presses the button and scary music shakes the kitschy doll, Nadja becomes frightened. “Why do you show me that!” Lucy becomes maternal, she takes her tarantella back. Nadja apologizes. “I’m anxious,” she repeats. They take photographs and play with sparklers. Fleeting joy. They turn on the stereo, My Bloody Valentine.

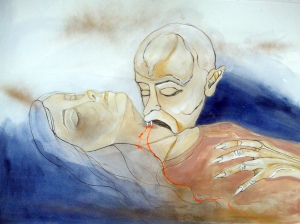

They make love in front of a mirror. They make love while Lucy’s on her period. (I’ve always wondered why I had never seen menstruation represented in vampire fiction before.)

They make love under pixilation.

Scenes of passion are all pixilated, shot with a Fisher Price Pixilvision, to represent alienation, how we only know the world from our perspective, how we try to communicate with others and what gets lost in the translation. Almereyda wants to remind us that we’re voyeurs, and we’re only human. There’s so much we can’t know. Vampires aren’t human, they feel their kin’s pain, they know, they understand, for a moment, when they receive the psychic fax, what it’s like to be somebody else. We don’t have that luxury, or curse, if you’d rather. As humans, we translate, we empathize, but we don’t know, we can’t see, our psychic vision’s blurry.

Nadja doesn’t want to kill her. She’s in love, she tells Renfield, who’s in love with her, his maker. He asks her how she knows. “Because I feel terrible.”

The pain of fleeting joy.

Renfield doesn’t want Nadja to turn Lucy, but he has no choice. He is Nadja’s slave, he loves her as the original Renfield loves Dracula, his master. Lucy is as Lucy does, is almost turned. She’s not herself, she’s sick, dying, pining, struggling, zombified.

Nadja goes to her twin brother, Edgar. He’s also dying. He’s also in love with a mortal, Cassandra, his nurse. His love is requited, and for that, or because of that, Edgar hates himself. He wants to die. Nadja convinces Cassandra to bring Edgar to their father’s house in Manhattan. She tells Cassandra that she and Edgar have the same disease, that she’s not dying, that Edgar just needs his special medicine, shark embryos, she says.

Lucy is lost in a trance of forced obsession. Jim finds her at a copy shop (the same one I printed my graduate thesis at!), and leads her to the bar Nadja had picked her up at.

“We can be totally honest? There’s no point in anything, right? And lately I’ve been feeling so disconnected from everything. I take long walks, I go to the park. Sunsets help, somehow. Calendar art, the cornier the better. Once or twice a day I see a woman on the subway I think I can fall in love with. No reason, except, I like her face, her hands, her neck. Then I come home and you’re there and I realize I should be completely happy. I mean, today, seeing you sick, I got so worried. I felt so helpless. All I know is I want to be with you forever.” Jim.

Lucy replies.

“Life is full of pain, but I’m not afraid. The pain I feel is the pain of fleeting joy.” Lucy.

Lucy’s gone. First mentally, then physically. She flees, comes to Nadja’s call. Jim is concerned. He follows her. Van Helsing wants to kill Nadja and Edgar, he thinks he’s leading the charge. He still thinks it’s his narrative. But really, he’s just in the way. Jim doesn’t care about vampires, or Dracula, or all the terrible, mystical horrors surrounding him. He doesn’t care about killing Nadja. He just wants Lucy back. But she’s gone.

“She can’t sort out her feelings. She can’t tell the difference between caring and wanting, emptiness and hunger, loneliness––” Jim

Edgar receives a psychic fax from Nadja, who has taken Cassandra to their homeland, to Transylvania, by the Black Sea, in the shadow of the Carpathian Mountains. They all travel to Transylvania, just as the crew in Dracula travels to Transylvania. They use Edgar’s connection to Nadja to locate them, just as Mina’s connection to Dracula is her crew’s compass. Just like her father, Nadja’s emotions are like big storms. Just like her father, Nadja is killed. Just like her father, Nadja’s spirit lives on.

Again, the plots of Nadja and Dracula intersect just as the characters and themes intersect. Nadja takes a little bit of everything it wants, but instead of the philosophical question of morals that the Victorian age obsessed over, Nadja reflects the jaded spirit of the nineties, with its existential angst, apathetic malaise, and narcissistic ennui. Cassandra’s monologue is a mirror.

“The problem is we’ve lost our spirituality. We’ve lost contact with ourselves and what our purpose of existence is. We’ve lost contact with God, and I don’t mean God as a man with a beard, a father, a punisher, but God as a source, a spirit, a stream of energy and light that links all things. We feel empty. We have a huge hole in ourselves. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t have a huge emptiness in their lives. We look away otherwise you start acting yourself, Why does one day merge with another day? Why does a black night gather in the mouth? Why all these people dead?” Cassandra.

P.S. Netflix‘s description of Nadja is inaccurate.