As seen circulating around the blogosphere, Ten Most Influential Books. In no hierarchic order. These are the books I hold nearest and dearest. These are the books that shaped me as a writer, and as a person.

1. Henry and June by Anaïs Nin.

Ms. Nin came to me at a liminal time when I was deciding whether or not I would write. Up until this point I had only written journals, diaries, or really terrible, sincere poetry. Writing was something secretive, something I did in shame. Ms. Nin taught me that the subjective experience is beautiful, universal, important. She unapologetically writes like a woman, with such abundance and honesty. She is a creator, a mother, a goddess. Her insights on the terrible joys of her own disintegration inspired me for decades to record and observe everything that mattered to me.

I want to be a strong poet, as strong as Henry and John are in their realism. I want to combat them, to invade and annihilate them. What baffles me about Henry and what attracts me are the flashes of insight, and the flashes of dreams. Fugitive. And the depths. Rub off the German realist, the man who “stands for shit,” as Wambly Bald says to him, and you get a lusty imagist. At moments he can say the most delicate or profound things. But his softness is dangerous, because when he writes he does not write with love, he writes to caricature, against something. Anger incites him. I am always for something. Anger poisons me. I love, I love, I love.

2. Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson.

Wittgenstein’s Mistress is a canonical expression, a postmodern acceleration of the great modernist thematics of alienation, solitude, social fragmentation, and isolation. “In the beginning, sometimes I left messages in the street,” the first line reads, says, because one does get the sense that Kate is speaking to you, that she needs you. She is the last person – the only living being – on earth. There are no other Beings off of whom Kate can bounce her identity anymore. She can no longer anticipate the kind of unpredictable future that an Other could bring. She is stuck in the present, only able to refer to the past (particularly, the literary past). She is the soul keeper of all of humanity, responsible for the cultural sphere of memory, which includes art and history, subjects which once belonged to everyone. She types up all that she can remember, as it relates to her conscious thoughts. Trying to relate all of this, every fact she can remember, Kate types, to herself, to no one, for herself, for humanity, one fragment at a time, with such precision that she begins to lose the thread. Wittgenstein’s Mistress taught me about allegory, about the boundaries of the novel, and about the slippery nature of language. This is the best representation, I can think of, of the human mind, how it remembers and how it communicates.

Wittgenstein was never married, by the way. Well, or never had a mistress either, having been a homosexual.

Although in the meantime when I just said in the meantime I truly did mean in the meantime.

It now being almost an entire week since I additionally said I would doubtless think of my cat’s name in a day or two.

3. The Melancholy of Anatomy by Shelley Jackson.

Melancholy of Anatomy is a collection of short stories that turn the body inside-out. Each organ or bodily abjection she depicts becomes conscious, dangerous, symbolic of our bodies as a mélange, as fragmented, as fragile. She creates a fantasy world where giant ovum suddenly appear outside, sperm fly through the air like insects, and menstrual blood gushes through pipes. When I was assigned this back in college, I had yet come across a wedding of Écriture feminine and fantasy, most of the contemporary feminine writing I had seen was essay about writing, I couldn’t recall any fiction. In Melancholy of Anatomy, every line delivers a new idea, playing off of the last, enriching, filling her stories to the brim with equally gorgeous and uncomfortable squishy goodness. Her prose is tense, both academic and playful, and though the rest of the class complained she was pretentious, I couldn’t have fallen more in love with Jackson’s rich text, her courageous style and subject matter, and her endlessly sharp mind. Later, when I studied under her, I was just as in awe.

There are hearts bigger than planets: black hearts that absorb all light, hope, and dust particles, that eat comets and space probes.

4. The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being opens with Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return, that maybe, possibly, every moment in our agonizingly detailed life will be repeated again and again in the exact same manner forever. Sometimes, that thought is too much, too heavy. But then again, if we do only live once, then it may as well never happen. This was my first flirtation with nihilism, with death and meaninglessness, all concepts that seem incredibly grim, but I also found them inspiring. I wanted to live my life like an art project. For years I told people that this was my favorite book, I thought it made the world a better place simply by existing. I related to every character: Tomas and his omnipotence, his hubris; Tereza and her physical insecurity, her ontological insecurity; Franz and his passion, his quixotries; but mostly, I identified with Sabina, because I used to consider myself a mistress, and an artist. She was everything I wanted to be: unencumbered, powerful, sincere, authentic. It was such a pleasure to pretend that for the longest time she was my primary role model.

When they looked at each other in the mirror that time, all she saw for the first few seconds was a comic situation. But suddenly the comic became veiled by excitement: the bowler no longer signified a joke; it signified violence: violence against Sabina, against her dignity as a woman. She saw her bare legs and thins panties with her pubic triangle showing through. The lingerie enhanced the charm of her femininity, while the hard masculine hat denied it, violated and ridiculed it. The fact that Tomas stood beside her fully dressed meant that the essence of what they both saw was far from good clean fun (if it had been fun he was after, he, too, would have had to strip and don a bowler hat); it was humiliation. But instead of spurning it, she proudly, provocatively played it for all it was worth, as if submitting of her own will to public rape; and suddenly, unable to wait any longer, she pulled Tomas down to the floor. The bowler hat rolled under the table, and they began thrashing about on the rug at the foot of the mirror.

5. Nightwood by Djuna Barnes.

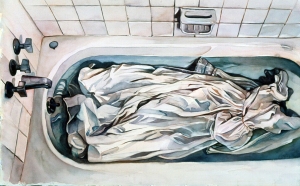

It was a toss up for me, deciding between Nightwood and Ryder, but in the end I came down on Nightwood. It’s perfect. The kind of perfect that’s almost discouraging. Christopher Hitchens says this about Nabokov. Djuna Barnes says this about Joyce. I’m saying this about her. She takes the high modernist style and appropriates it into her own. Jeanette Winterson writes that “reading [Nightwood] is like drinking wine with a pearl dissolving in the glass.” Queer and blasphemous. Gothic and lyrical. Rich and dazzling. Plotless and wise. Barnes’ prose renders me speechless. She was unapologetically opinionated, boner-shrinkingly powerful, and always in a tremendous amount of pain. Nightwood is essentially a roman à clef about Barnes’ devastating relationship with Thelma Wood, who is only thinly disguised as Robin Vote.

Sleeping in a bed, surrounded by plants and exotic flowers, heavy and disheveled, we first meet Robin, who is described with such beauty, such longing, such ache. This woman can love.

The perfume that her body exhaled was of the quality of that earth-flesh, fungi, which smells of captured dampness and yet is so dry, overcast with the odour of oil of amber, which is an inner malady of the sea, making her seen as if she had invaded a sleep incautious and entire. Her flesh was the texture of plant life, and beneath it one sensed a frame, broad, porous and sleep-worn, as if sleep were a decay fishing her beneath the visible surface. Above her head there was an effulgence as of phosphorus glowing about the circumference of a body of water–as if her life lay through her in ungainly luminous deterioration–the troubling structure of the born somnambule, who lives in two worlds–meet of child and desperado.

Like a painting by the douanier Rousseau, she seemed to lie in a jungle trapped in a drawing room (in the apprehension of which the walls have made their escape), thrown in among the carnivorous flowers as their ration; the set, the property of an unseen dompteur, half lord, half promoter, over which one expects to hear the strains of an orchestra of wood-winds render a serenade which will popularize the wilderness.

Nora, my protagonist in A Suburb of Monogamy, is an homage to Ms. Barnes.

6. Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha.

Dictee is a nonlinear, multilayered, fragmented, cyclical text written in white ink. Like the painful, beautiful act of giving blood, the novel’s life force transfers from one body to another. One heroine to another. Always becoming. The self dissolves into, with, because of, the transmutability of selves. Dictee opened up new worlds of structure for me. It redefined the novel, yet again, but in ways beyond Markson, beyond House of Leaves, beyond language. Dictee is a work of art, an experience. Everything Hélène Cixous had ever taught me I was now seeing in Dictee. Cha, as a displaced Korean woman, writes in a borrowed tongue, mainly in her allotted English language, but also several others, because she has no language of her own, and because she wants her readers to experience the “in between.” Something is always lost in even the most direct (impossible!) translation, even in the translation of thought to language. Cha effectively illustrates that all women’s words are veiled, exposed as being cloaked in mystery, but still, it’s better to speak, even under a veil.

Dictee is a nonlinear, multilayered, fragmented, cyclical text written in white ink. Like the painful, beautiful act of giving blood, the novel’s life force transfers from one body to another. One heroine to another. Always becoming. The self dissolves into, with, because of, the transmutability of selves. Dictee opened up new worlds of structure for me. It redefined the novel, yet again, but in ways beyond Markson, beyond House of Leaves, beyond language. Dictee is a work of art, an experience. Everything Hélène Cixous had ever taught me I was now seeing in Dictee. Cha, as a displaced Korean woman, writes in a borrowed tongue, mainly in her allotted English language, but also several others, because she has no language of her own, and because she wants her readers to experience the “in between.” Something is always lost in even the most direct (impossible!) translation, even in the translation of thought to language. Cha effectively illustrates that all women’s words are veiled, exposed as being cloaked in mystery, but still, it’s better to speak, even under a veil.

Cixous asks women to break through Phallogocentrism; start an aphonic revolt; leave not a single space untouched within language that is man’s alone. She wants us to “dislocate this annihilating within….explode it…impregnate it!” Cha does exactly this. Each one of her images, her allegories, all begat another, then another; her words open up like flowers, each carrying a precious seedling, and ready, at any moment, to spread their love.

Lift me to the window to the picture image unleash the ropes tied to weights of stones first the ropes then its scraping on wood to break stillness as the bells fall peal follow the sound of ropes holding weight scraping on wood to break stillness bells fall a peal to the sky.

7. His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman.

I finished each of these three books the same way: on the sixteenth hour, pacing back and forth across my living room floor, laughing, gasping, crying, keeping myself awake, just to finish, because I couldn’t stop, because I didn’t want them to end.

I finished each of these three books the same way: on the sixteenth hour, pacing back and forth across my living room floor, laughing, gasping, crying, keeping myself awake, just to finish, because I couldn’t stop, because I didn’t want them to end.

Both Pullman and his novels are renowned atheists. He took the questions of God, consciousness, and the beginning of life, and he answered them. As a child, I was raised Catholic. Catholic school and everything. At a young age I began to question my faith. Then I began to fear death, which I began to think of as non-existence, pure blackness, meaninglessness. And this terrified me. Heaven wasn’t reassuring because I didn’t believe in heaven. I could’ve used His Dark Materials to help answer some of those torments. He masterfully illustrates that for some, simply returning to the earth is preferable to what could quite possible turn out to be a celestial North Korea. Pullman’s God character is not God but the first being to become conscious of himself. A tyrannical regime that splits children from their souls has been erected in his honor, and it’s up to a little girl, her daemon (which is an animal manifestation of her soul or psyche), and some friends to help save all the creatures in all the worlds that are conscious of themselves. This takes guts. His Dark Materials is a magical, thoughtful, and perspicacious book, and what I really like, is that Pullman shows that morality does not solely lie within the church, that it is an inherent quality to intelligence and love.

As Mary said that, Lyra felt something strange happen to her body. She found a stirring at the roots of her hair: she found herself breathing faster. She had never been on a roller-coaster, or anything like one, but if she had, she would have recognized the sensations in her breast: they were exciting and frightening at the same time, and she had not the slightest idea why. The sensation continued, and deepened, and changed, as more parts of her body found themselves affected too. She felt as if she had been handed the key to a great house she hadn’t known was there, a house that was somehow inside her, and as she turned the key, deep in the darkness of the building she felt other doors opening too, and lights coming on. She sat trembling, hugging her knees, hardly daring to breathe, as Mary went on:

Note: If you’re going to buy His Dark Materials make sure you get a British edition as all American presses censored The Amber Spyglass. Above is the censored paragraph.

8. Introduction to Phenomenology by Dermot Moran.

Opening this book for the first time meant discovering Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Levinas, Gadamer, Arendt, Merleau-Ponty, and Derrida within five minutes. It was almost too much. I remember shutting the book, smoking a bowl, then beginning again. In a reductive nutshell, Phenomenology is the study of things in their manner of appearing to consciousness. The mode of givenness is best approached when assumptions about the world are put out of mind, bracketed off. This is a study that gets back to the building blocks of existence. One must now think of objects as existing exactly in the manner in which they are given in the view from nowhere. Meaning, all objects are encountered perspectivally and “inside” each and all objects there are an infinite number of perspectives. For instance, my cat and I see a rubberband very differently, as does my boyfriend, and my mother. Though we all have an idea of rubberbandness, we each have memories of specific rubberbands we’ve encountered that go into play each time we look at a new rubberband, or remember a rubberband. This study is also put to other beings, Others, as well as the self. Phenomenology is a kind of science; it must be attentive to describing the mode of being as accurately as it can, while at the same time aware that it can only know its own subjective experience. Husserl sought pure description, which led to Heidegger’s historicity and temporality, which then of course led to Derrida’s Deconstruction, which, for all intensive purposes collapsed phenomenology as a method. Derrida attacked the assumption of the possibility of the “full presence” of any meaning in an intentional act, which then emphasized the displacement of meaning, the constant deferring of meaning, therefore eliminating any possibility of pure meaning.

Opening this book for the first time meant discovering Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Levinas, Gadamer, Arendt, Merleau-Ponty, and Derrida within five minutes. It was almost too much. I remember shutting the book, smoking a bowl, then beginning again. In a reductive nutshell, Phenomenology is the study of things in their manner of appearing to consciousness. The mode of givenness is best approached when assumptions about the world are put out of mind, bracketed off. This is a study that gets back to the building blocks of existence. One must now think of objects as existing exactly in the manner in which they are given in the view from nowhere. Meaning, all objects are encountered perspectivally and “inside” each and all objects there are an infinite number of perspectives. For instance, my cat and I see a rubberband very differently, as does my boyfriend, and my mother. Though we all have an idea of rubberbandness, we each have memories of specific rubberbands we’ve encountered that go into play each time we look at a new rubberband, or remember a rubberband. This study is also put to other beings, Others, as well as the self. Phenomenology is a kind of science; it must be attentive to describing the mode of being as accurately as it can, while at the same time aware that it can only know its own subjective experience. Husserl sought pure description, which led to Heidegger’s historicity and temporality, which then of course led to Derrida’s Deconstruction, which, for all intensive purposes collapsed phenomenology as a method. Derrida attacked the assumption of the possibility of the “full presence” of any meaning in an intentional act, which then emphasized the displacement of meaning, the constant deferring of meaning, therefore eliminating any possibility of pure meaning.

Each and every idea in this book was mind-blowing for me and led to such an exploration of so many concepts. I initially wanted to include Sartre’s The Imaginary on this list, then I thought I needed Derrida, and I couldn’t decide on any specific text, but really, I should pay homage to the very book–even though it’s an introduction–that started it all. The Introduction to Phenomenology made me a better thinker and a better writer and I know of no other academic book that has had such a profound impact on me.

It is frequently argued that the main contribution of phenomenology has been the manner in which it has steadfastly protected the subjective view of experience as a necessary part of any full understanding of the nature of knowledge.

9. Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll.

This is the only book I’m including from my childhood. Though SO MANY books shaped me and inspired me, Alice never stopped amazing me. I loved that the protagonist is a little girl, and that she’s on a genderless journey, I laughed at how rude everyone is; then later I loved the drug references, then analyzing the Freudian implications of Carroll keeping Alice locked outside of the garden, her sexuality, so at least textually, he could keep her as a little girl forever. Then, I became obsessed with the linguistic games–how mathematical he made language–then how many of the metaphors and scenes relate to Carroll’s migraines, a disease both he and I share. However, the more I love this book the more I lament how often it’s been represented in the lesser medium of film. To reproduce Alice is almost a sign of being washed up. *Ahem*Tim Burton*Ahem* Alice is a book that’s meant to be read. Its riddles are meant to confuse a child, and the implications of those riddles are meant to confuse an adult. Though the latter’s confusion is to be much more pernicious and therefore much more liberating. All this, all the scholarly supplemental reading, and all the flights of fantasy I took on its behalf are why Alice must make the list.

This is the only book I’m including from my childhood. Though SO MANY books shaped me and inspired me, Alice never stopped amazing me. I loved that the protagonist is a little girl, and that she’s on a genderless journey, I laughed at how rude everyone is; then later I loved the drug references, then analyzing the Freudian implications of Carroll keeping Alice locked outside of the garden, her sexuality, so at least textually, he could keep her as a little girl forever. Then, I became obsessed with the linguistic games–how mathematical he made language–then how many of the metaphors and scenes relate to Carroll’s migraines, a disease both he and I share. However, the more I love this book the more I lament how often it’s been represented in the lesser medium of film. To reproduce Alice is almost a sign of being washed up. *Ahem*Tim Burton*Ahem* Alice is a book that’s meant to be read. Its riddles are meant to confuse a child, and the implications of those riddles are meant to confuse an adult. Though the latter’s confusion is to be much more pernicious and therefore much more liberating. All this, all the scholarly supplemental reading, and all the flights of fantasy I took on its behalf are why Alice must make the list.

“Must a name mean something?” Alice asked doubtfully.

“Of course it must,” Humpty Dumpty said with a short laugh: “my name means the shape I am–and a good handsome shape it is, too. With a name like yours, you might be any shape, almost.”

10. Hamlet by William Shakespeare.

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.–Soft you now!

The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remember’d.

Hélène Cixous also deserves an honorary mention. The mother of Écriture feminine, a more emboldened strain of feminism, Cixous has encouraged women to inscribe their bodies, and their difference, into language and text. Many have shown me the importance of writing, but she has shown me the importance of writing as a woman, a feminist, and an othered member of society. She is in a different category, on a different plane of existence. Everything I have read of hers has changed my writing, has inspirited and incentivized me. She is my most beloved artist.

Hélène Cixous also deserves an honorary mention. The mother of Écriture feminine, a more emboldened strain of feminism, Cixous has encouraged women to inscribe their bodies, and their difference, into language and text. Many have shown me the importance of writing, but she has shown me the importance of writing as a woman, a feminist, and an othered member of society. She is in a different category, on a different plane of existence. Everything I have read of hers has changed my writing, has inspirited and incentivized me. She is my most beloved artist.

Censor the body and you censor breath and speech at the same time. Write yourself. Your body must be heard.