I had decided, as an adjunct to Bataille’s Erotism, I would read Bram Stoker’s Dracula, but, given vampirism’s relationship with sexuality and Catholicism, the side project mushroomed into something of its own accord. For the next couple of posts I’ll be unpacking various texts surrounding Dracula, starting, of course, with Stoker, then moving on to Coppola’s 1992 film, Guy Maddin’s silent ballet: Dracula; Tales from a Virgin’s Diary, Nadja, and finally, Dodie Bellamy’s The Letters of Mina Harker. As usual, though plot isn’t at the forefront of my concern, it shall however be revealed as I discuss the more alluring pieces of these texts.

I had decided, as an adjunct to Bataille’s Erotism, I would read Bram Stoker’s Dracula, but, given vampirism’s relationship with sexuality and Catholicism, the side project mushroomed into something of its own accord. For the next couple of posts I’ll be unpacking various texts surrounding Dracula, starting, of course, with Stoker, then moving on to Coppola’s 1992 film, Guy Maddin’s silent ballet: Dracula; Tales from a Virgin’s Diary, Nadja, and finally, Dodie Bellamy’s The Letters of Mina Harker. As usual, though plot isn’t at the forefront of my concern, it shall however be revealed as I discuss the more alluring pieces of these texts.

[…]

Vampires are neither dead nor alive. They are undead, or, Undecidable: a puncture in the Life/Death dichotomy, waffling between life and death, undermining and subverting hierarchical order, marking and signifying the structures and limits to binary oppositional thought. The desire to kill a vampire is not to abolish the hedonism vampires represent, or rather, suffuse (restoring straitlaced Victorian prudishness), but, as Derrida suggests, to return the world back to a system of order.

Just as humans are driven to love they’re also driven to die.

That being said: it’s not death we abhor, it’s chaos.

Vampires as figures, as myths, had been around for centuries before Stoker’s creation of Count Dracula in 1897. Based partly on Vlad Ţepeş/Vlad the Impaler/Vlad Dracula the warrior prince of Wallachia, partly on the aristocratic and charismatic nosferatu in John William Polidori’s The Vampyre, partly from Varney, the Vampyre by James Malcom Rymer, but mostly Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 Carmilla, the story of the gorgeous and charming vampire Countess Mircalla posing as Carmilla, and her fatal tryst with the lonely, ingénue Laura.

Dracula is an epistolary novel, meaning, it’s told entirely through journal entries and letters. So just as Dracula has no reflection in the mirror, the narrator(s) cannot reflect him either. He is never recorded in “real time.” The reader can only see (experience) him through misty and unreliable subjective memories, the veils of anecdote.

Dracula exists only as an afterthought.

But an afterthought our male characters are Hell-bent to destroy.

Though the Count is only in a small fraction of the text, his presence can be felt through out. His specter permeates the entire narrative in the negative, through negative space He is what is not being said like a shadow to the action, walking death, a toothsome vagina in which our characters boldly traverse to protect their women, their livelihood, their sacred act of procreation, the God-given right to penetrate a nonthreatening toothless vagina, manhood intact, in control, on top of the hierarchy, Missionary-style.

That fine line… Sex is Life / Sex is Death.

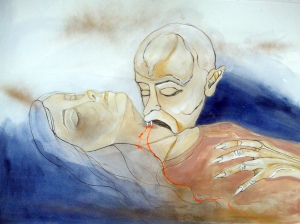

“With [Dracula’s] left hand he held Mrs. Harker’s hands, keeping them away with her arms at full tension; his right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. Her white night-dress was smeared with blood, and a thin stream trickled down the man’s bare chest which was shown by his open dress.” Stoker. Dracula.

Each time we engage in the act of sexual intercourse, the brain goes through a moment of cognitive dissonance. On an unconscious level we wish to clone ourselves, live forever, but, obversely, we also want to obliterate ourselves, become one with the flow of the continuity of Being, dissolve into the great cosmos. We wish to fertilize, create another life, another death, pass along the existential torch to an unnamable baby, our pleasure centers are teeming with abundance, stretching at the seams, tumescent to the point of rupture. Then the crown of jouissance erupts, explodes in a paroxysm, annihilating our egos, our wills, sometimes, even our sight. In orgasm, we are our bodies, nothing more. We are simply here. Pure Being, like a dish of mold. In orgasm, the state, the quest of Eros is fulfilled, blowing open a door for Thanatos to slip into.

Percy Bysshe Shelley refers to the orgasm as “the wave that died the death which lovers love.”

La petite mort. A miniature death, a taste.

La petite mort. A miniature death, a taste.

With each passing night, as Dracula visits Lucy, draining her of her life-blood, she experiences a miniature death as part of herself leaks out, passes from her body to his lips. Giving one’s life, the ultimate act of eroticism that parallels the sacrament.

“Life is always a product of the decomposition of life.” Georges Bataiile Erotism: Death and Sensuality.

A simple formula. The life cycle. It’s fascinating and horrible when it’s disrupted, when natural laws and social taboos are violated. Dracula combines the two Christian taboos of sex and death. He transgresses his own humanity and rises to the level of a god through steeping to the rung of a carnivorous animal; a sexual predator romanticizing the moment of death; eating the kill, not the meat. The victim is stripped of her clothes, her identity, and her will. She is under a spell, in a trance, hypnotized to a Bacchanal frenzy, begging for defilement. Her hymenal neck is penetrated, her life-blood is drained, satiating his hunger, giving him life. Sustaining his existence.

“In Dracula, vampirism is—to be pedestrian in the extreme—a metaphor for intercourse: the great appetite for using and being used; the annihilation of orgasm; the submission of the female to the great hunter; the driving obsessiveness of lust, which destroys both internal peace and any moral constraint; the commonplace victimization of the one taken; the great craving, never sated and cruelly impersonal. The act in blood is virtually a pun in metaphor on intercourse as the origin of life: reproduction; blood as nurture; the fetus feeding off of the woman’s blood in utero. And with the great wound, the vagina, moved to the throat, there is, like a shadow, the haunting resonance of the blood-soaked vagina, in menstruation, in childbirth; bleeding when a virgin and fucked. While alive the women are virgins in the long duration of the first fuck, the draining of their blood over time one long, lingering sex act of penetration and violation; after death, they are carnal, being truly sexed. The women are transformed into predators, great foul parasites; and short of that, they have not felt or known lust or had sex, been touched in a way that transforms being—they have not been fucked.” Andrea Dworkin. Intercourse.

Dworkin, of course, is arguing that once women taste the forbidden fruit of lust they become demonized, sex-crazed monsters, femme fatales, Sirens, Lilith, and therefore, must be destroyed. Women are supposed to be submissive, passive, pale and weak, tight-laced, painted, primmed and demure. Lucy, in other words. Not Mina, because Mina is the New Woman, a partner in every sense, but still devout and dedicated to both God and her husband. “Ah, that wonderful Madam Mina! She has man’s brain – a brain that a man should have were he much gifted – and woman’s heart,” gushes Dr. Van Helsing, who also had said:

“She is one of God’s women, fashioned by His own hand to show us men and other women that there is a heaven where we can enter, and that its light can be here on earth. So true, so sweet, so noble, so little an egoist – and that, let me tell you, is much in this age, so skeptical and selfish.” Van Helsing, Stoker.

Mina is the epitome of the perfect Victorian woman. She represents all that Dracula threatens to destroy. To play devil’s advocate with Dworkin, one can argue that Stoker was a feminist. He even heralds some queer themes. And while I do commend Stoker for being ahead of his times concerning issues of gender and sexuality, essentially Dracula is still a heteronormative text. With the Count, his fangs, his cock, as the fundamental patriarch. Logos shrouded in Eros.

Mina is the epitome of the perfect Victorian woman. She represents all that Dracula threatens to destroy. To play devil’s advocate with Dworkin, one can argue that Stoker was a feminist. He even heralds some queer themes. And while I do commend Stoker for being ahead of his times concerning issues of gender and sexuality, essentially Dracula is still a heteronormative text. With the Count, his fangs, his cock, as the fundamental patriarch. Logos shrouded in Eros.

Vampirism, the great, sharp, protruding fangs are symbolic for the phallus, while the pale, heaving necks supplant female genitalia. Thus gender roles are flipped when Jonathan Harker is seduced by the three vampire women. He writes:

“I was afraid to raise my eyelids, but looked out and saw perfectly under the lashes. The fair girl went on her knees, and bent over me, fairly gloating. There was a deliberate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive, and as she arched her neck she actually licked her lips like an animal, till I could see in the moonlight the moisture shining on the scarlet lips and on the red tongue as it lapped the white sharp teeth. Lower and lower went her head as the lips went below the range of my mouth and chin and seemed to fasten on my throat. I could feel the soft, shivering touch of the lips on the supersensitive skin of my throat, and the hard dents of two sharp teeth, just touching and pausing there. I closed my eyes in a languorous ecstasy and waited – waited with beating heart.” Jonathan Harker, Stoker.

Just as Victorian society feared a sexually aggressive, predatory, sexually assertive female, Jonathan Harker is both attracted and repulsed by the women vampires (just as Mina is to Dracula). But still, Stoker reversed the gender roles, yet in doing so, maintained the power structured of the traditional binary opposition: Light vs. Dark. Good vs. Evil. Cock vs. Cunt.

bell hooks writes on this branch of feminism, where women become men to assert equality and enact dominance, in her book Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, Chapter 2: “Power to the Pussy: We Don’t Wanna Be Dicks In Drag.” Using a photograph of Madonna brandishing a strap-on dildo climbing on top of Naomi Campbell, hooks argues that though Madonna as a name, a symbol has become synonymous with Girl Power and rebellion, taking the amaranthine mother, the holy virgin, and subverting that name, Madonna, to extrapolate the virgin/whore dichotomy of our culture. Instantly, Madonna was a hero to feminists, but, ultimately, hooks says, she only claims power by adopting masculine traits and genitalia. For Madonna, there is no power to the pussy, just a claim that pussies can be dicks too. (Though, an essential step in the sexual revolution and women’s equality––that can’t be dismissed––however, feminists should move beyond this line of thinking and reclaim their pussies as powerful in and of themselves. Reappropriation is more powerful than imitation. ‘Tis why I love Écriture Féminine.)

“The whole business of eroticism is to strike to the inmost core of the living being, so that the heart stands still. The transition from the normal state to that of erotic desire presupposes a partial dissolution of the person as he exists in the realm of discontinuity… In the process of dissolution, the male partner has generally an active role, while the female partner is passive. The passive, female side is essentially the one that is dissolved as a separate entity. But for the male partner the dissolution of the passive partner means one thing only: it is paving the way for a fusion where both are mingled, attaining at length the same degree of dissolution.” Bataille.

All victims of vampirism are cunts. The cunts are subsumed into the vampire, who, while in the throngs of ecstasy, forget themselves, devolve into pure predators, whose orgasm is life-affirming, as the victim’s orgasm is more of a L’appel du vide: a desire, a drive to leap into the abyss.

Because, as we all know, a cunt is a void and all voids need to be filled (ravaged).

Such is order.

Such is the state of being’s irreconcilable and oppressive loneliness, our own fundamental isolation. We try to fill that hole. We throw food into it, clothes, cars, football, narratives, anything that can be fetishized, loved. We even try to fuck our way out of it, fuck ourselves to the brim. I’ve heard pregnancy helps ease the pain. I expect that when one carries another, nihilism shrinks as a new purpose becomes so immediate and obvious. (A philosophical way to look at postpartum depression?)

“Beings which reproduce themselves are distinct from one another, and those reproduced are likewise distinct from each other, just as they are distinct from their parents. Each being is distinct from all others. His birth, his death, the events of his life may have an interest for others, but he alone is directly concerned with them. He is born alone. He dies alone. Between one being and another, there is a gulf, a discontinuity.” Bataille.

This gulf, Bataille says, is hypnotic, meaning, we are hypnotized by our own deaths. The “Death Drive” in Freudian terms; “Being-Towards-Death” in Heideggarian.

So both Lucy and Mina are drawn to Dracula. They want him to touch them, to feed them and feed off of them. They welcome it L’apel du vide Lucy, the compliant female, the perpetual virgin, especially. Mina is more reluctant. She’s disgusted with Dracula, she hates and detests him, but she doesn’t quite fear him, she pities him, and though this baffles her, she’s drawn to him, she wants him, and he already has her:

“My revenge is just begun! I spread it over centuries, and time is on my side. Your girls that you all love are mine already; and through them you and others shall yet be mine – my creatures, to do my bidding and to be my jackals when I want to feed.” Dracula, Stoker.

Dracula is a god. A Dionysus figure, a murderous parasite, raw sexuality, hedonistic, red-blooded, animalistic, sadistic, father of death and carnal lust. His existence will corrupt the Victorian sensibilities, he will demolish and massacre the sacred order of life, the Christian hierarchy of things.

Dracula is a god that must be sacrificed.

For the love of God.