“Women must write through their bodies, they must invent the impregnable language that will wreck partitions, classes, and rhetorics, regulations and codes, they must submerge, cut through, get beyond the ultimate reserve-discourse, including the one that laughs at the very idea of pronouncing the word ‘silence,’ the one that, aiming at the impossible, stops short before the word ‘impossible’ and writes it as ‘the end.’ ” (Cixous 2049)

“May I write words more naked than flesh, stronger than bone, more resilient than sinew, sensitive than nerve.” Attributed to Sappho, written by Cha[i], who then later writes, she is “exchangeable with any other heroine in the story.” (30)… Sybil. Demeter. Persephone. Gertrud. Princess Pari. Queen Min. Yu Guan Soon. Joan of Arc. St. Therese of Lisieux. Laura Claxton’s sister. Clio. Calliope. Urania. Melpomene. Erato. Elitere. Thalia. Terpsichore. Polymnia. Mnemosyne. Hyung Soon Huo. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. Daughter. Mother. Unnamable Women.

Dictee is a nonlinear, multilayered, fragmented, cyclical text written in white ink,[ii] an act of giving blood. The life force transfers from one body to another. The self dissolves into, with, because of, the transmutability of selves.

Before we recognize the fluidity of selves and language, there must be a brief paragraph given to the “Word,” the “One.” This Signifier[iii], this One, has been all pervasive, has dominated social structures, linguistic structures, and narrative structures. Everything was (arguably still is) in a hierarchy. The binary structure of opposition. In short, there is a cage match.

In the red corner: Man! With his… speech, immediacy, presence, light, truth, logos, oneness, his God and his penis.

And.

In the blue corner: Woman! With her… deferral, difference, absence, darkness, lack, lawlessness, multiplicity, her heterogeneity, and her vagina, that terror.

But. The blue corner never wins.[iv] She’s been doomed, damned, cunt-shunted. So she’s kept quiet, silent, living in veils and shadows, wrapping herself in shawls and enigmas. This is where Cixous asks women to break through, start an aphonic revolt, leave not a single space untouched within language that is man’s alone. She wants us to “dislocate this annihilating within….explode it…impregnate it!” (Cixous 2049) Cha does exactly this.[v]

She writes in a borrowed tongue, in her allotted English language, and several others, but asks the reader to translate (part of) the text into French. This is not written solely for a bilingual audience; she wants the reader to experience the “in between.” Her side-by-side prose of English and French[vi] requires something to be lost in the (impossibly) direct translation. French to English, and vice versa, will never be, it cannot be exact. Her words, no matter the language, are then veiled as well, exposed as being cloaked in mystery, proving that that the invisible is complicated, but not unexplorable.

Silence, Mnemosyne[vii], memories, passivity, waiting, they’re all part of the invisible. Cha describes the pain of waiting inside a pause, waiting inside herself, as unbearable. “The wait from pain to say,” (4) she says, the mute diseuse, who secretly waits within their structure, multiplying, wrapping every word in tinfoil or black lace. She lives inside the void, inside the terrifying in-between structure, the space where the she makes her voice, gets the strength to speak. Just to speak.

This is not a matter of castration, of control, of winning, but rather the point is to “dash through and to fly.”[viii] (Cixous 2050) Woman’s subversiveness is her own anonymity. Cixous claims women are givers, they can merge without annihilating themselves, flow from one woman to the next. “Her language does not contain, it carries.” (Cixous 2052) Words blend from one word to the next. Women, like words, are alive because they transform. They are always becoming.

“The woman arriving over and over again does not stand still; she’s everywhere, she exchanges.” (Cixous 2056) In other words, she is a metamorphosing collage of multiple voices. Cha’s (re)writing history, embodying the Muses, giving them voices, freeing them from their original patriarchal shackles, and this includes not making them speak only through men, in their male language, with their phallologocentric stories of beginnings, middles, and ends, their epic poems.

All Cha’s figures, all her narratives, begin in the middle; they always relate to another story: the Mother.

Dictee is not a traditional epic poem. It is not about man’s rise to glory, the glory of the gods, or a best or first of anything.[ix] Helene P. Foley argues “that the female version of the heroic quest is defined by issues relating to marriage and fertility and ends with a cyclical reunion and separation that also mitigates death.”[x] Dictee’s Muses no longer conceal their sorrow. They illustrate that there is something inherently traumatic in the female position.

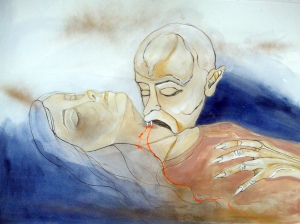

Cha speaks of a series of concentric circles, which can be translated to a series of returns and departures, a code of trauma, meaning both the traumatic event is cyclical, perpetually returning to haunt the survivor contemplating the impossibility of their own death, and also that one’s own trauma is tied up with the trauma of another. Trauma has a mute repetition of suffering,[xi] a festering silence, a wound. “Trauma seems to be much more than a pathology, or the simple illness of a wounded psyche: it is always the story of a wound that cries out, that addresses us in the attempt to tell us of a reality or truth that is not otherwise available. This truth, in its delayed appearance and its belated address, cannot be linked only to what is known, but also to what remains to be unknown in our very actions and our language.” (Caruth 4)

The wound is another, an Other, a foreign object inside the body[xii], a divided self. “It festers inside. The wound, liquid, dust. Must break. Must void.” (3) The Koreans, and women, do not own their imagery. They must dictate what is spoken to them using the oppressor’s language. They swallow the wound. It weeps.

Dictee is the wound crying out. And because it’s not fully understood, because it’s related to the suppression, to a mini-death, the speech comes out broken, in fragment – without the attempt at sewing them together. To create links is to manipulate; to do as the oppressors do. According to écriture feminine,this is a masculine trait of dominance, and consumption.[xiii] The one creating the links is the one that controls the image-repertoire. Cha, like Cixous, is requesting a new mode of reading, a new mode of listening, not a new language.

This is further explored with Cha’s use of curtailed images of suppressed history. Anne Anlin Cheng suggests that “redeeming these images has frequently only served to re-violate them.” (Cheng 121) The repressed no longer own the images of themselves. These images become images of the action, belonging to the oppressors. Cheng follows with both the urgency and the impossibility of rerecording history, echoing the mindset of Caruth: History arises within the impossibility of understanding.

Cha is (re)presenting the trauma of an entire nation and the female gender. Both language and image are insufficient to accurately describing the horror, the subjugation, the effacement. “Unfathomable the words, the terminology: enemy, atrocities, conquest, betrayal, invasion, destruction.” (32) These words are the opposite of Cha’s epitaph, they do not recognize the irony of their own stability as words. The act of seeing these images reappropriated into Japanese history, or hearing the empty signifier, erases the reality of any event. Cha is preventing that from happening again; she’s preventing the reoccurrence of removal by not attempting to explain, to master. The image, like trauma, cannot be mastered. This is an embrace of the cyclical quality of trauma, its arrivals and departures, the series of concentric circles.

Through her analysis of Hiroshima Mon Amour, Cathy Caruth discusses a similar situation about both Korea’s oppressors. “The knowledge of Hiroshima, for the French, understood not as the incomprehensible occurrence of the nuclear bombing of the Japanese but as the knowledge they call ‘the end,’ effaces the event of a Japanese past and inscribes it, as a referent, into the narrative of French History.” (Caruth 29) Cha understands that this is a nationwide, corrosive occurrence. The postmodern subject has a difficult time grounding herself within the constructs of the image and the reappropriations of words, languages, and texts. The abstract enemy, the relationship between self and enemy, becomes larger because of what’s at stake: total consumption. In the language of binary opposition, the enemy is all that the self is not, and therefore, runs, and fears the constant risk of its own “ontological security.”[xiv]

The self recognizes itself as a being in the world, inextricably dependent on that world, and not the other way around.[xv] People exist as beings defined by Others who carry models of us in their heads, just as we carry models of them in our heads. Laing explains that a schizophrenic turns herself into a “thing”[xvi] to reduce herself from being in the world. When one’s identity is constantly being threatened, and because the being relates to the world through her body, she disembodies herself to transcend the world and be safe.

If Dictee’s subject(s): Woman qua silence, qua subservient, Other, separated from Mother, from Motherland, experiences a double separation, double subservience, then what is lost turns into loss. The reader is asked to empathize, particularly during Calliope’s segment where the text is written in second person, but Cha refuses to let the reader get grounded in a particular protagonist, a particular subject. Cha seeks to break down the representation of trauma as liminality. Both Dictee and trauma deny any sort of mapping within the ontological framework; R.D. Laing would consider this kind of division schizophrenic.

I would argue this “divided self” represents yesterday’s woman,[xvii] the woman that turns herself into an object, that defines her sexuality only through the male gaze, through the masochistic desire to be looked at; this is the woman that completely identifies with the androcentric stagnation of masculine “Truth.”

The Freudian system of sexuality is based on looking because it privileges the penis,[xviii] thus privileging the visible. This masochism is forced upon the woman, meaning pleasure does not reside in her, but refers back on male sexuality.

Luce Irigaray reminds us that the very nature of woman’s self, her sexuality, is auto-erotic, in that the woman is constantly touching herself[xix] since her vagina is composed of two embracing lips. She says that with herself, woman is already two, and not divisible into one, and she translates this feminine auto-eroticism into feminine discourse or writing. “This ‘style’ does not privilege sight; instead it takes each figure back to its source, which is among other things tactile. It comes back into touch with itself in that origin without ever constituting in it, constituting itself in it, as some sort of unity… It is always fluid, without neglecting the characteristics of fluids that are difficult to idealize: those rubbing between two infinitely near neighbors that create a dynamics.” (Irigaray 79)

According to Irigaray, the feminine “style” of writing is filled with ebb and flow, multiple beginnings, and multiple paths. And this is what Cha emphasizes with the nonlinear narrative of her female heroines, all of which transcend the patriarchy, all of which ebb and flow into one another.[xx] This nonlinear approach interferes with historical practice, which is most ironically portrayed by Clio. Not only does Cha connect historical events with fragments of Guan Soon’s biography, she also literally rewrites history in order to voice a history from a woman’s perspective.[xxi]

Every character loops around and connects to every other female character through the omnipresent trope of the mother-daughter relationship. And she mythologizes her “real life characters” in order to make the personal public, thus furthering the subversion of the epic poem.

Each woman is connected through various mothers as well as their refusals to yield to the oppressive patriarchal forces of imperialism. The Elysian Fields, to which Cha alludes to, are not just a place of heavenly female experience, but a place of real heartache as well. Cha promotes the experience of woman by trickling one woman into the next in such a way as to disrupt all linear assumptions by deleting the bridges history deems necessary to create.

The nonlinear is deeply connected with the unnamable in that there is no determinable beginning or end, and without the abrupt packages the masculine “style” creates, all “Truth,” in its phallologocentric forms, is unraveled and taken away from its inherent morbidity. Men have thought that the only two unrepresentable things are death and the female sex,[xxii] but Cha shows that the female sex is not unrepresentable, it was just unrepresentable within the oppressive confines of the masculine system of referents. But now the ironclad chain linking the signifier and signified is broken.

Again, this breaking is not a violent castration, but a delicate process of veiling and unveiling. As a woman’s body may become “full” with child, language, words become full with double meanings. The Freudian binary system of sexuality explodes with this addition of multiplicity. And by the very definition of multiplicity the penis is not excluded, just no longer privileged. Cha is refusing to call herself, which at this point includes all women, a lack, a nothing: “transform this nothingness into fire.” (111) She wants love to lower itself to nothingness, to the realm of the woman, for a true and total union. Echoing the words: “I do desire the other for the other, whole and entire, male or female; because living means that everything lives, and wanting it to be alive.” (Cixous 2054)

And in this transition, death cannot, and will not be privileged over life. A mother lifts her child up to the window. The daughter witnesses the pulleys, the machine, the language of her mother’s time; she wants to see, to become a part of it: “Lift me to the window to the picture image unleash the ropes tied to weights of stones first the ropes then its scraping on wood to break stillness as the bells fall peal follow the sound of ropes holding weight scraping on wood to break stillness bells fall a peal to the sky.” (179) Break the stillness. Break the silence. Perpetual motion. Perpetually becoming. Peal away the layers. Appeler: to name. A peal. A name. Peal a name back, reveal more than one, render the thing, the itness of it, and all that entails, indescribable, unnamable.

Bibliography

DICTEE. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. University of California Press. 2001.

UNCLAIMED EXPERIENCE; TRAUMA, NARRATIVE, AND HISTORY. Cathy Caruth. The John Hopkins University Press. 1996.

THE LAUGH OF THE MEDUSA. Hélène Cixous. THE NORTON ANTHOLOGY OF THEORY AND CRITICISM. W.W. Norton & Company. 2001.

THE SEX WHICH IS NOT ONE. Luce Irigaray. Cornell University Press. 1985.

THE DIVIDED SELF. R.D. Laing. Pelican Books. 1965.

REWRITING HESIOD, REVISIONING KOREA: THERESA HAK KYUNG CHA’S DICTEE AS A SUBVERSIVE HESIODIC CATALOGUE OF WOMEN. Kun Jong Lee. COLLEGE LITERATURE 33.3. Summer 2006. Pg. 77

MEMORY AND ANTI-DOCUMENTARY DESIRE IN THERESA HAK KYUNG CHA’S DICTEE. Anne Anlin Cheng. MELUS 23.4. Winter 1998. Pg. 119

End Notes

1 “One of the first female writers who put women into the text, world, and history was Sappho… Cha [also] manifests her feminist position by identifying with Sappho: she writes the epigraph herself and attributes it to the Greek poet.” (Lee 78)

[ii] Not an obscure, angry, flat, and unreadable feminist text.

[iii] Penis.

[iv] In reality, given the Master/Slave dialectic, neither ever wins.

[v] “She begins the search the words of equivalence to that of her feeling. Or the absence of it. Synonym, simile, metaphor, byword, byname, ghostword, phantomnation. In documenting the map of her journey.” (140) The double-meanings, the nonwords, the semantics game.

[vi] Dare I say two lips?

[vii] In the Theogony, Mnemosyne disappears after giving birth to the nine muses.

[viii] Voler: to fly and to steal. The double meaning was originally implied.

[ix] M.M. Bakhtin: “The world of the epic is… a world of bests and firsts.” (Lee 87)

[x] As explained by Kun Jong Lee on pg. 92.

[xi] In contrast to the language of pain: the scream, cavewoman utterances.

[xii] A Migraine.

[xiii] Whoever controls the present controls the past…

[xiv] Phrase coined by Dr. R.D. Laing describing people that feel persecuted by reality itself.

[xv] Unless you’re a solipsist.

[xvi] He gives various examples from patients, such as a piece of wood floating in a pond.

[xvii] Cixous’s woman of yesterday: the woman silently dwelling.

[xviii] Hence, penis envy.

[xix] As Dictee illustrates in Erato’s Love Poetry section.

[xx] All of which transcend the limitations of their bodily identities.

[xxi] Guan Soon did not organize the March 1st riots in Seoul, but in her hometown Aunae, nor were the March 1st riots started after the assassination of Queen Min, who was murdered 24 years earlier. Cha specifically manipulates these details because she truly “regards the Queen as the symbol of Korea colonized by Japan and situates her at the origin Korea’s nationalist struggle against Japanese colonialism.” (Lee 87) And Guan Soon was popularly called the Joan of Arc of Korea; Cha wanted to “situate Guan Soon at the origin of the March First Movement, to portray the ‘woman soldier’ as an active agent of history; and to recenter the feminine voice from the margins of Korean nationalism.” (Lee 87)

[xxii] Which to men, Cixous points out, is equal to death.